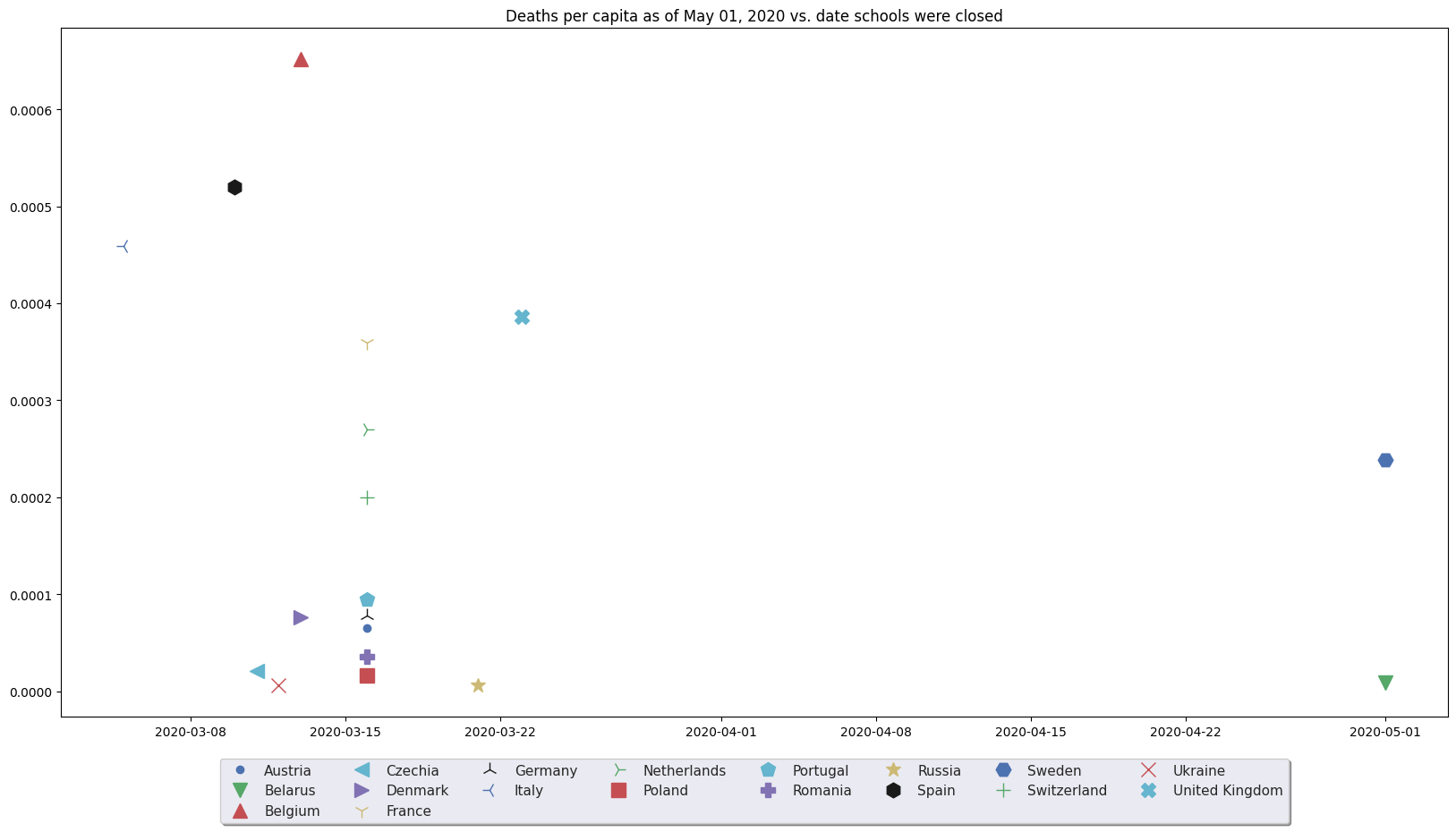

This week, I'm looking at the mortality rates as of the end of April, for a few dozen countries in Europe, and comparing it to the dates when they closed elementary schools. Now, I'm going to refer to this as "when they closed schools", but it should be noted at the outset that most countries closed a lot of other things at the same time. They often closed gyms, some retail, hair salons, and a lot of other parts of normal life. This also varied in the details from one country to another. What I'm going to use as a sort of proxy for all of this, is what date the elementary schools were closed. Partly, this is because it is the easiest thing to find out for all of the various countries with just a google search. But it is also something that serves as an indicator for a lot of other things.

Not every country in Europe is listed here, but we've got all of the biggest, and a good geographic range from north to south and east to west. The metric for Covid-19 I'm looking at is mortality, per capita, because that's what we really care about. It's probably also closer to the reality it's aiming to measure, than the metrics for infections, recovery, etc. I have the impression that these numbers are becoming more political as time goes by, but of all the metrics we have available, it's the best we have.

Because of the politics surrounding death rates in both China and the U.S., I'm wary of using data from either one. Also, there seems to be a continent-to-continent factor, with European mortality rates mostly being higher than western hemisphere nations, and asian nations being lower. So, by restricting the analysis just to Europe, we have enough countries to get a significant amount of data, and (sorry, there's no nice way to put this) enough deaths to make sure we have a better signal-to-noise ratio.

We also have two countries included, Sweden and Belarus, which did not close their elementary schools at all. We give them the date of today, so that they show up on the graph at least, for comparison. But in reality neither of these countries has closed their schools yet. Also, at least one, Denmark, has just reopened their schools; we are neglecting that here since it probably hasn't had time to impact the death totals one way or the other anyway.

With all that said, let's take a look.

Hmmm. Underwhelming. But, it's not too hard to imagine why. There are an obvious cluster of countries on March 16th, who probably were all doing it on that date in part because everyone else was, but otherwise it is not too surprising that the countries with the worst problems early, would be the ones to close earliest. Those countries are also, not surprisingly, the ones who have had the most total deaths (per capita), so that could be why this graph gives the impression that closing school early gave worse results.

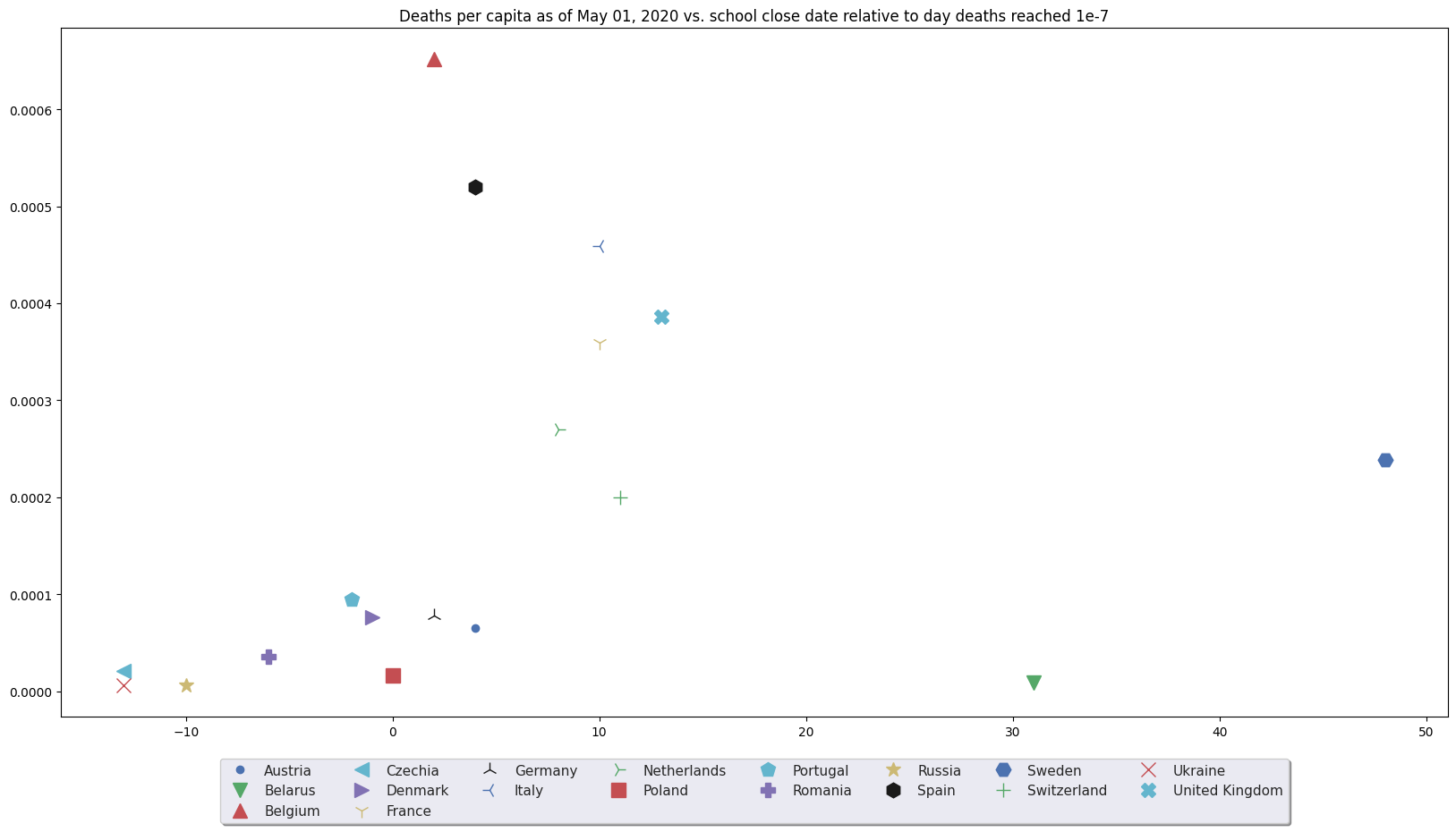

To compensate for this, I generate for each country a "day 1", which is the day on which total deaths first reached the level of 1 per 10 million people. This means that countries that closed earlier than this date, will have a negative number, while countries that closed after this date will have a positive number. Countries which didn't close at all will have a number equal to how many days it has been since their "day 1". The idea is that "day 1" is when things had just barely started, but they were far enough along to be significant.

Hmmm. Well there's a little bit more of a signal, in that the countries with a negative number have better results. However, the countries with a small (but positive) number of days before they closed, seem to do the worst, and the ones who waited longer to (or never did) close their schools, have more intermediate results. That's odd.

It could be, of course, that there is something to this. Perhaps there is a mechanism wherein, if you can close everything early enough, you should do it, but if you're too late to stop it, you should let the healthy ones roam around to reach "herd immunity" faster. The hope would be that you reach this before there's a chance for it to get into nursing homes and other vulnerable populations. It may be that, after you've had beyond a certain proportion infected, nothing will stop the virus except to get to herd immunity. Keeping it from reaching vulnerable populations is tricky, and maybe closing the schools just a little late, gets you the worst of both worlds. You can't stop the virus before it gets going, but you do slow down the process of reaching herd immunity, which leaves more days to screw up the isolation around the most vulnerable. But then, it occured to me that, since I had already calculated the "day 1" of each country, I might as well plot the mortality against that.

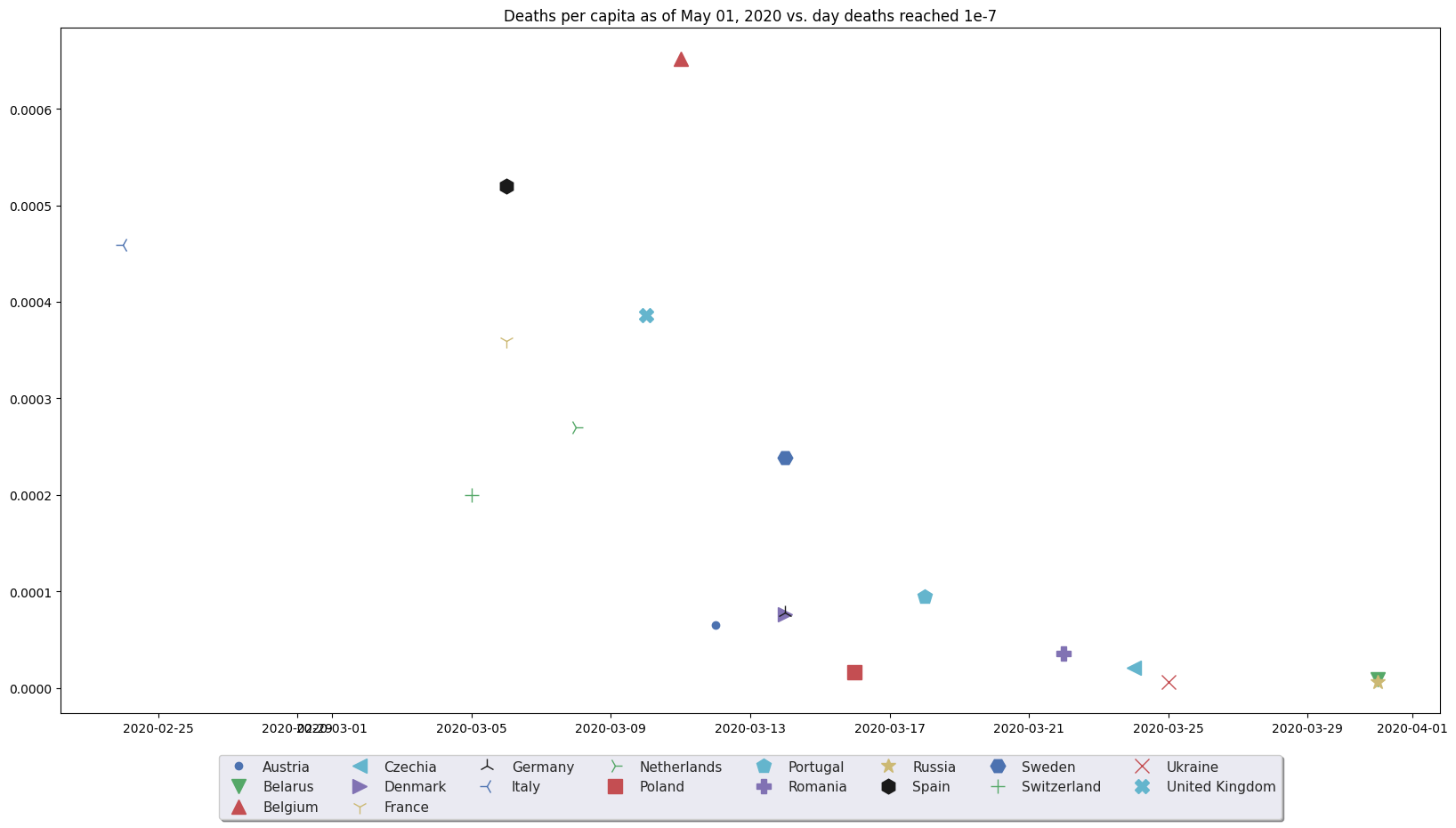

Ooh. Throw away that previous theory, this looks more like a real correlation. There is a clear relationship here. Oh, wait, I get it. The later countries just haven't had time to lose as many people yet. They just look like they're doing better, because it's earlier in the course of the virus for them. Well, the latest "Day 1" I have is for Belarus, and that was at the end of March, so we can just total up the 25 days from Day 1 to 24 days later, for each country. This means we will be looking at 25 days, total, for each country, starting from the day where deaths reached the level of 1 in 10 million.

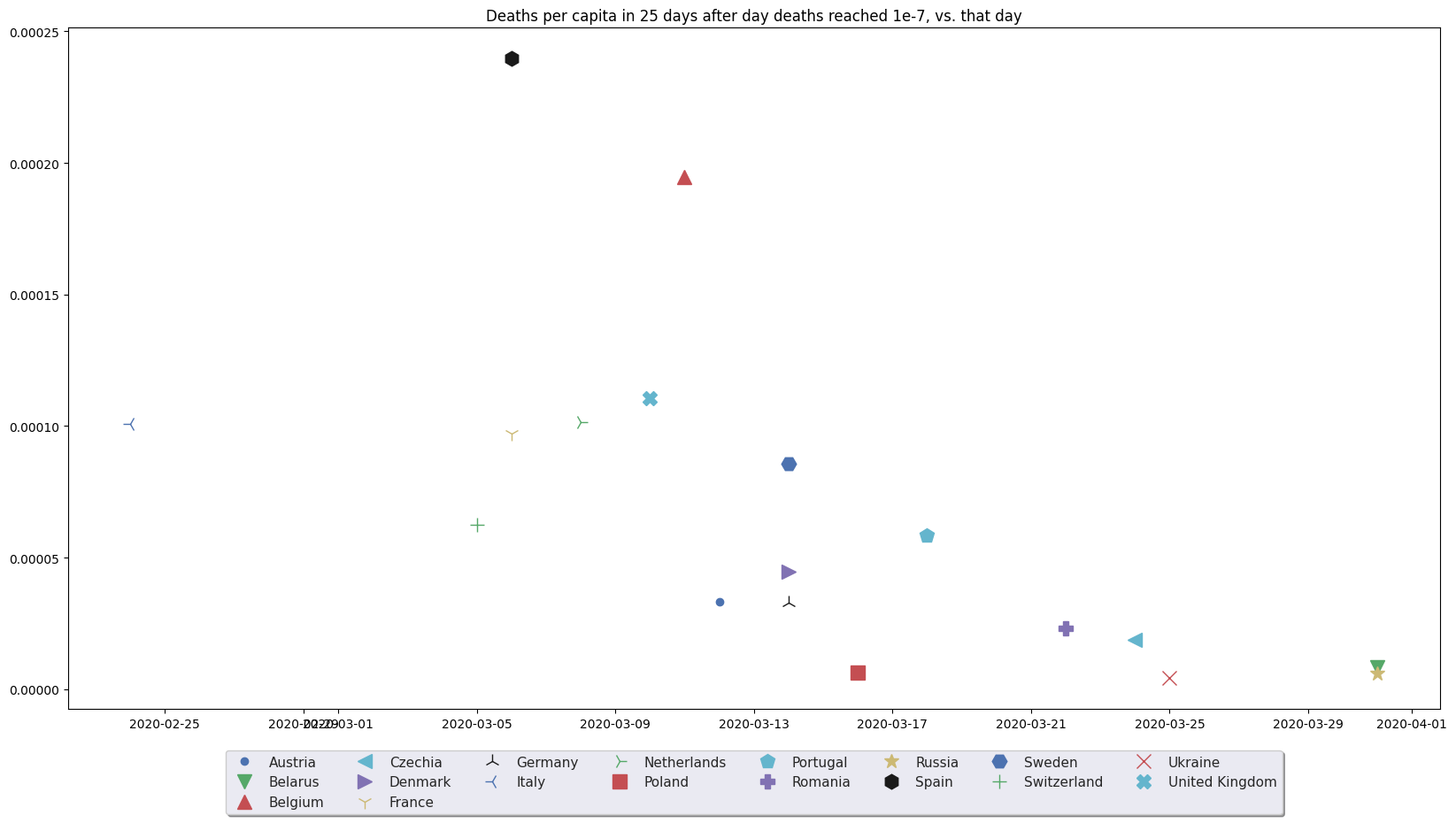

Whoa. The signal looks, if anything, even a tiny bit stronger. Could this be true? And if so, what would it mean?

It is a pretty well-known phenomenon, that novel diseases (including viruses) usually become less lethal over time. This is by no means a guarantee, and the mechanisms responsible are still debated. But, one possibility is related to the fact that most viruses (including the one that causes Covid-19) have multiple variants. The variants that are less lethal are more likely to have a host that walks around spreading it everywhere, whereas a more lethal variant is more likely to make its host stay put, reaching fewer new hosts. If the less aggressive variants spread faster than the more aggressive ones, then you are more likely to encounter the less aggressive variant first. If these variants are still similar enough that facing one teaches your immune system how to face the other, this would be a good thing.

So, the fact that Russia, Belarus, Czechia, and Ukraine had a later "day 1", may indicate that the virus had spread further through Europe before it got to them. Since the less aggressive versions would be likely to spread faster, the gap between less and more aggressive variants' arrival would be greater for these countries. By the time the more lethal version arrived, the less lethal version had been there awhile, and some of the population was already immune. Poor Italy, Spain, etc. got the most aggressive form early, and had little or no exposure to a less aggressive (but more quickly spreading) version to prepare them.

At this point, I want to point out that while the data above is from the excellent John Hopkins repository, itself aggregating data from a variety of national and international institutions, the theory I just gave is basically just me thinking out loud.

It does, however, raise a question about the wisdom of putting the healthy population under lockdown, once you have reached the point (long since arrived in every nation of Europe) that the disease is too widely spread to extinguish. I imagine "fight fire with fire" must have seemed crazy to people whenever the first person suggested, "wow this fire is out of control now, there's no way we can stop it with water or shovels at this point. Hey, you know what we should do? Start another fire!" But, while a spark landing in the tinder should be snuffed out as quickly as possible, at some point in the course of a raging inferno you need to admit that the time for that strategy has passed, and it's time to use backburning or something similar.

Because if the people with the less aggressive variants stay home, and the people with the more aggressive variants go the hospital (where there are other potential hosts, and in some cases a shared ventilation system to spread it to them), then you could reverse this process, and cause the more aggressive variant to spread faster than less lethal ones. This is the opposite of what we want.

Fortunately for us, it is probably all a moot point, as I'm not convinced that the lockdowns of various forms have really impaired the ability of the virus, in any of its variants, to spread. Standing in line at the grocery store is probably not all that much better than going to a restaurant and remaining seated at your table. The above data regarding school closures also shows that even Sweden and Belarus, with very different policies from other nations in Europe, don't look all that unusual (either better or worse) than the rest of Europe. This is especially true once you account for the dates that the dying started in each country.

But, if we see the death rates start to spike up again, because the lockdown has selected for the most virulent (pun intended) forms of the virus, I guess I would have to revise my opinion on that.